The Ricciardo Sisters

The story of Italian Sisters: Dora and Margherita Mackin - with references to Velia Campbell, (all nee Ricciardo).

Avezzano village

https://cdn.britannica.com/72/129172-050-6638BE8F/Castel-del-Monte-Italy-region-Abruzzi.jpg

I was born on the 22 August, 1929, in a village called Avezzano about one and a half miles from Sessa Aurunca. The village is under a mountain, called Massico, and near the sea, about 40 miles from Naples. There are 36 small villages around Sessa Aurunca in the Campania region.

My dad, Guiseppe, aged 21 years, in 1920.

https://congruenceengine.yarncommunity.org/storage/Sisters_Father_Guiseppe_1920_1658856110.jpg

My father had been the only person in our village (and many of the other villages) who had never worked for someone else. He worked over a wide area visiting other villages and assessing the value of their olive and grape crops.

He also owned fields that grew olives and grapes and with the people he employed to farm these crops he followed the system known as Mezzadria (half and half) where the profits from the crops were shared between the land owner and those planting and harvesting the crops.

In my dad’s case he only took one third of the profits. My dad had purchased an electric machine to grind the olives before pressing these. I remember that it was 1935 when my village got electricity. In those days only the black olives were used and pressed for the production of virgin olive oil. We had to wait until the ripe fruit had fallen to the ground.

Stramma Grass

https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0299/4729/7931/files/92e23c_large.jpg?v=1579201183

Dad’s business also used the harvested grasses or stramma that grew in abundance on the mountain side. The smaller bushes and narrow stalks were used for basket and rope making and the larger bushes, with wide stalks, were used for mattress filling.

The stramma for basket making was beaten with a tool like a large rolling pin, a mazzuco, to soften it and this stramma was also pulled into twine and plaited for rope making. My dad was able to use the electric olive press to process the larger stramma stalks. These larger stalks were combed first in a machine, twisted and then dried in the sun. After drying they were pressed electrically to soften them and form the filling for mattresses.

We made a box to feed these ropes into the press and they came out as bales. The roof top of our house was used to dry the rope. A large wagon came to our house every fortnight to collect the processed bales.

Documentary showing the plight of refugees in WWII Italy.

https://youtu.be/d6uvHRiLhMY

All my family worked inside to help with this part of dad’s business. We were the only family that did not work for other people. My dad was affectionately known as Don Peppino by the local people.

Sadly, another man who had been dad’s competitor for some time, eventually talked him into going into partnership, but this man later cheated my dad. My dad had agreed to his new partner keeping the books for the business and, unknown to dad, he had bought a shop and a house in his wife’s name. As a result, at the end of a bad season for crops, there was no money in the business to pay bills or debts.

My dad had to sell fields to pay bills for all the farmers and to help pay some of the overdrafts. Also the use of stramma for mattress filling was dying out rapidly as new materials began to be produced for this purpose. It broke my dad’s heart when his children then sought work overseas to support the family.

Italy Surrenders US newsreel

https://youtu.be/Bak672iXZC8

I was one of 9 children, one of whom died in 1939. I had little memory of the Second World War, other than a memory of the celebrations when the armistice was agreed in 1943. In those days, no –one bought ready-made clothes. Everyone bought material and all clothes were hand-made.

We had a lovely childhood in many ways. Every July and August, until 1943, the family rented an apartment in Scauria, where we also had a cabin on the beach to get changed in. Our cabin was numbered five – the same number as our house – so that we children would easily recognise this number.

All the family worked for my dad and we employed other people but after my dad went bankrupt in 1956 we all needed to think of ways to help the family finances.

My brother, who was attending University in a nearby town called Caserta had heard from a man from our village, Pietro Tuozzi (who worked in the labour office in Caserta and travelled on the same train with him daily) that some English textile companies were seeking girls to work in their mills and he had told him that for the girls selected the fares and costs would all be paid for by the firm who was recruiting Italian girls.

The people depicted here in 1949 were soon to start working in the British textile industry. 55 Italian women embarked upon a train from London to Lancashire, where they would be trained as weavers within the scope of the ‘Westward Ho’ scheme. Proposed by the British Minister of Labour, this scheme was directed toward European Voluntary Workers: continental Europeans invited to come work in the UK after World War II.

https://images.ctfassets.net/i01duvb6kq77/d1bfcfbb3568e7d599e34467da0b3307/9b1fb2c8ee1021a20c4c8f935dd700b0/Italian_girls.jpg?w=1100&q=80&fm=jpg&fl=progressive

Velia and I were able to weave grasses and also to make ropes so we had experience in pulling and twisting twine with electric machinery.

We checked this out in the labour exchange in Caserta and my sister Velia and I were allowed to travel to Naples to be interviewed by two people from England. 200 girls from around the area attended these interviews that were conducted over two days. We all stayed in a camp just outside Naples – it was like a holiday camp in some ways. We had to undergo x ray examinations, blood tests, eye tests and other medical examinations and answer many questions about our families. Around seven doctors examined us and it was a bit degrading.

When this process was completed we had to return home and wait for a telegram to inform us as to whether we had been accepted. In this case, only 16 girls were chosen. The telegram for myself and my sister Velia arrived on a Wednesday and we had to leave home on the following Sunday so we had to go to Caserta immediately to get our passports.

The passport office opened especially for this on the Saturday and my cousin took us there. I was 27 years of age and Velia was 25 years old.

You may find this PhD useful in understanding the experience of female migrants in the UK textiles industry:

Italian women migrants in post-war Britain: the case of textile workers (1949-61)

Gasperetti, Flavia (2012). Italian women migrants in post-war Britain: the case of textile workers (1949-61). University of Birmingham. Ph.D.

You can find it here: https://etheses.bham.ac.uk/id/eprint/3417/

Henry Mason Mill

https://congruenceengine.yarncommunity.org/storage/Screenshot_2022-07-26_at_19.22.00_1658859769.png

Velia and I went to Milan by train and had to be medically examined again to check we weren’t pregnant. We met two girls from our village, Elisa and Jose, in Caserta and we all travelled by bus to Rome. From Rome we travelled to Milan to catch a train that took us to Calais in France, we got on the ferry to Dover – we didn’t get to England until the Wednesday, arriving at our hostel on Otley Road, Shipley, at 10pm that night. We arrived in March 1957.

When we arrived in Dover there were two men and two Italian women (Maria and Yola) waiting to meeting us on behalf of the mill. They took all 16 of us to a coffee shop. They had a post card of the mill, ready stamped for us to send to our families to say that we had arrived safely.

The mill we had been recruited to work at was Henry Mason’s mill in Shipley (it was situated on the site adjacent to the Inland Revenue Office)

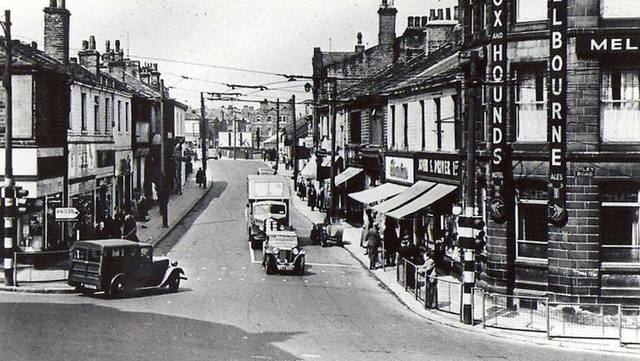

Shipley late 1940's.

https://www.closedpubs.co.uk/yorkshire/pics/shipley_foxhounds.jpg

Although my sister Velia and I came together, another sister Margherita had also wanted to come to work in England but she was too young being only 19 years of age. Once I, Dora had got a contract from the mill however, it was possible for Margherita to come as Velia and I could take responsibility for her.

Margherita recalls - ‘I had to go through the full range of demeaning medical examinations in England, before going through customs, and had to travel to England alone. I recall that, as a teenager, the whole journey was very exciting – an adventure. I missed the train I was due to catch in London and asked a policeman for help as best I could. The policeman was very helpful and found an Italian speaking person who found out where I could stop for the night and catch a train the next day. All I had was a £5 note but I got very good help. After Arriving in Shipley, (in March 1958) I went to work the next day’.

‘I remember that, whilst travelling on the train through England I thought that the houses all looked the same but the further North the train got, the blacker the houses became’.

Anti migrant racism in the UK in the 1950s.

https://youtu.be/bzDItpuBcEg

They wrote home to their family in Italy every week – using the telephone was too expensive – and kept this up until their mother, Elena died in 1995.

Elena wrote frequently to the sisters keeping them up to date with local news and any births, deaths or marriages in the village.

Dora and Margherita state that they now think and dream in English and have lost their past fluency in the Italian language – having to think carefully about how they say things when speaking to other members of their family.

They both are clear however that they have had a happy life and that they would not change how life has been for them in England.

They wrote home to their family in Italy every week – using the telephone was too expensive – and kept this up until their mother, Elena died in 1995. Elena wrote frequently to the sisters keeping them up to date with local news and any births, deaths or marriages in the village. Dora and Margherita state that they now think and dream in English and have lost their past fluency in the Italian language – having to think carefully about how they say things when speaking to other members of their family. They both are clear however that they have had a happy life and that they would not change how life has been for them in England.

From The Ricciardo Sisters

A copy from the record book kept by Dora of the amounts of money the sisters were able to send home.

https://congruenceengine.yarncommunity.org/storage/Note_of_money_sent_home_1658856092.jpg

Nevertheless, initially Dora and Velia had been able to send £20 a month home and, when Margherita arrived in England to work, they were able to send £30 a month home to their father and mother – each contributing £10.

The sisters lived in a hostel built to house the Italian mill girls that was situated on Otley Road, near the Baildon traffic Lights. There were 8 girls already living there and we 16 newcomers increased the number to 24 in the hostel. The sisters recall that living in the hostel was great fun except for the need to share a kitchen with very limited facilities. Eventually this hostel was extended to become home to 40 young Italian women.

The Matron and her husband, Mr. and Mrs. Stebbins looked after all the girls – they had a daughter of their own, Mavis – now Taylor. They took the Italian girls shopping, helped with any necessary paperwork and making phone calls, and they ensured each girl had a doctor and a dentist. The girls paid 15 shillings each for rent, gas and electricity and eventually for an extra 6 pence per week had a television. The girls tended to take it in turns to clean the kitchen but cooked their own meals.

Salt's Mill interior

https://www.yorkshirepost.co.uk/images-a.jpimedia.uk/imagefetch/http://www.lep.co.uk/webimage/Prestige.Item.1.113151695!image/image.jpg?width=1200&enable=upscale

The girls were aware of a much bigger hostel, situated at the turn from Otley road into Coach Road, where many more girls and women were accommodated. This hostel was for C. F. Taylor’s Mill. They also remember that Salts Mill had at least one similar hostel.

They attended Belle Vue upper school on Wednesday and Thursday evenings to learn English, though these lessons were not compulsory. At work they got by with sign language at first and did make many English friends but the language barrier was very hard at times. ‘It was always nice to get back to the hostel were we could all understand one another’.

From bottom to top, Velia, Dora and Margherita, have their first photograph taken in the grounds of the Baildon hostel.

https://congruenceengine.yarncommunity.org/storage/F1-173a_001_1658856023.jpg

The English classes did help but Dora and Margherita found their husbands to be the most helpful and they recall that their conversational English improved after two years or so. Dora found reading the Daily Mirror helpful also.

Their contract with the mill was for 1 year initially and the company paid the fare home after this year for girls who did not want to stay any longer. Later, in 1960, their two younger sisters, Gina and Maria, also came to work in textiles but they didn’t settle and returned home after 6 months.

Other memories of these early days included their first experience of ‘bonfire night’, which seemed strange because in Italy fireworks are used on Christmas Eve. The mill also arranged a trip to Blackpool for its workers every year which was also memorable.

St Aidan's Church - Baildon.

https://taking-stock.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2019/03/baildon.jpg

Dora, Velia and Margherita continued to work in England and all eventually married there. Margherita was the first to marry, meeting her husband Alan in 1959 and marrying in March 1960. Dora was to find her future husband in Alan’s brother, Peter, who was in the army when Margherita met Alan. Dora and Peter married in October 1961 and Velia married an Irish man, Hughie Campbell, in February 1961 who worked as a builder, in Shipley. Hughie had lodged at the same place as Alan and Margherita, after they were married, and that is how Velia met him.

The first time the sisters went home was after three and a half years in England and they saved up to go for 6 weeks in August 1960, to have an Italian ceremony for Margarita and Alan’s wedding. The mill paid for 2 weeks of that period but the remaining four had had to be saved for. Alan was amazed atthe way Italian men were treated ‘like kings’ and didn’t have to fetch and carry water, make coffee, wash up and so on.

The sisters didn’t register for British Citizenship until 1967 and initially, they lost their Italian citizenship, though this was conferred back to them in 1994, enabling them to have dual citizenship.

All three sisters were married in St. Aidan’s Church in Baildon, by Father Villani (from the Italian Mission in Bradford) and all their children went to catholic schools, initially St. Walburga’s primary school in Shipley

https://congruenceengine.yarncommunity.org/storage/The_sisters_with_Matron,_hostel_grounds_1658856126.jpg

They wrote home to their family in Italy every week – using the telephone was too expensive – and kept this up until their mother, Elena died in 1995.

Elena wrote frequently to the sisters keeping them up to date with local news and any births, deaths or marriages in the village.

Dora and Margherita state that they now think and dream in English and have lost their past fluency in the Italian language – having to think carefully about how they say things when speaking to other members of their family.

They both are clear however that they have had a happy life and that they would not change how life has been for them in England.

https://congruenceengine.yarncommunity.org/storage/F1-173a_003_1658856067.jpg

https://congruenceengine.yarncommunity.org/storage/14.2_The_Ricciardo_sisters_1956_at_home_with_their_family_1658856005.jpg

Postscript:

Elena had always written poetry whilst alive and Dora’s grandson Liam has kept up this tradition. Liam has Alstrom Syndrome, which has led to him becoming blind. His poetry is remarkable and he has had two books of poetry published.

Grandad

My Grandad is a funny man

He causes trouble whereever he can If somethings wrong he will play pop No matter what the type of shop

He has an attic and a cellar

He really is a splendid fella

He makes brilliant corned beef sandwiches And speaks 3 different langauges

In his cupboard is Tia Maria

Which is saved just for Christmas cheer Brandy, Martini, bottles of wine

He polishes the surfaces till they shine

He has a walking stick with badges on From places like Portmeirion

He has a badge of Caernarfon too And even one of the north Wales zoo

My granddad is really fine

And I’m glad that he is mine

He needs to know what I want him to And the message is ‘I love you’